A TELEPHONE shrills in the Brewery Fire Brigade night quarters at 84 James's Street.“There's been an accident.”“Where?”“In the brewery yard at the old weighbridge.”“How many injured?”“Two men.”“Badly?”“I don't know.”“Right, we're on our way!”The four-man team pile into the ambulance stationed outside and in a matter of moments are at the scene of the accident. Accident? Well, not a real one on this occasion. To keep the members of our Fire Brigade on their toes a competition is staged annually to provide practice in rescue technique. This year seven teams, each of four members, had been drawn out for the contest and the two teams of finalists were going through their paces in the presence of the Board.Conditions made as true to life as were possible and on arrival the rescue teams discovered two men trapped in a crater beneath a pile of planks and rubble, which had collapsed on top of them.Under the searching gaze of Dr. Eustace, F. W. Derbyshire and Dan O'Brien they go into action One man, still conscious, whose leg is trapped beneath a plank, presents the symptoms of a compound fracture; the other (a dummy) has the signs of a skull injury.Praise is due to John McGuirk of the Rigging section, a most realistic casualty whose acting lent an authentic touch to the proceedings.Both units displayed a high standard of proficiency, but the judges finally decided in favour of Team A, led by Edward King, with Dermot Harnett, James Scallan and James Duffy giving able support. Sir Geoffrey Thompson made the presentation to the winners at a short ceremony in the Fire Station afterwards.We in the Brewery have indeed reason to be thankful that we have such a well-trained group of men on hand, should a real accident call them into action.The Harp – Spring 1963

Work was a dangerous place in the past, and certainly for those who worked in industrial spaces full of noise, distractions, heat, and time pressure, then add to that toothed and spinning machinery, elevated gangways, and equipment literally on an industrial scale. Many workers were taking their lives in their hands every day that they showed up for their job, and although it would be incorrect to say that there were no safety measures in place in the 19th and early 20th century, there were certainly far fewer procedures and checks in place than we would expect to see in any factory are large processing plant today.

The above quoted training procedure from the Guinness brewery in Dublin demonstrates that breweries in Ireland were certainly as dangerous a place to work as any other similar sized and focussed enterprise, perhaps even more so, due to the oversized buildings and equipment which needed to be scaled in numerous ways at various times, and also the use of hot liquids and other unseen hazards as we shall see.

Breweries could be unforgiving and deadly places at times, and please note that this article will deal with and describe some of those deaths so those who feel uncomfortable with these types of descriptions should probably not continue.

-o-

The newspapers of the 1800s and early 1900s are dotted with reports of deaths in Irish breweries to the point where almost every decade had a report or two of workers being killed on or off site. It is, even at this remote juncture, a difficult read, as many of the reported inquests go into the details of precisely what happened these individuals, and often include a list of the people they have left behind, where sometimes, almost an afterthought, the reporter will mention the wife, children, parents or siblings that were left in heartache and possible destitution at the loss of a loved one. It is worth remembering at all times that we are dealing with actual human beings who lived not terribly long ago and who possibly still have ancestors walking our streets whose lives were affected directly or indirectly by such a dreadful occurrence.

Deaths appear to have happened in almost every brewery in this country and from multiple causes. Falls were quite common, with brewery workers - or at times hired contractors - tumbling to their deaths from the gangways that stretched across the upper reaches of the tall brewery structures. Falling from the top of the various brewing vessels was a hazard, as was falling from the roofs of the buildings themselves. At times the unfortunate individuals tumbled into mash tuns, kettles and other hot water sources, or fell close to lit boilers and suffered agonising scalds or burns that more often than not resulted in death.

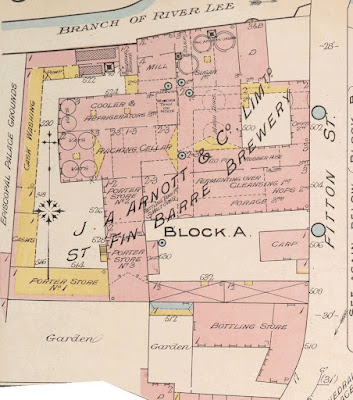

Drownings in porter vats, wells or water tanks also occurred, and in the case of the deaths in vessels which held beer, the owners of the breweries were forced to comment on the fact that the porter within was dumped, due to scurrilous reports of the beer still being put out for sale after the event. In 1874, at the inquest into the drowning of a worker in a vat of porter in St. Fin Barre's Brewery in Cork, Mr. Thomas Lane felt the need to put on the record and into the local paper that 'an injurious report has gone abroad that we stocked a quantity of the porter, whereas it is all gone down the river.'

There were rarer fatalities too, such as the man who suffocated in barley in Perry’s brewery Rathdowney in 1906 when he stood in a hopper containing grain which was then then tipped into a larger silo along with the worker and he was smothered by more grain being added while the unfortunate man was still inside it, something similar had occurred in Guinness in 1895 too.

There are also particularly gruesome accounts of workers becoming entangled in a piece of machinery in the brewery with the obvious and unrepeatable horrific injuries that this would entail. One particularly poignant report from 1867 tells of an 11-year-old boy who while visiting his father’s place of work – the Beamish & Crawford brewery in Cork – was caught in the cogs of machinery. He lost a leg amongst other injuries and died later in hospital.

One form of death that seems to have been dreadfully common was death by carbon dioxide suffocation, where a worked descended into a fermenter to clean it out without realising that it was full of this deadly odourless gas, a byproduct of the fermentation process, which can incapacitate a person almost instantly. This type of death was relatively common, and some of the fatalities recorded in this way were in an unnamed Cork brewery in 1782, Guinness’s in 1839 and 1864, Lane’s brewery Cork in 1846, Wickham’s in Wexford in 1869, Jameson and Pim’s in 1894, Darcy’s in 1898 and 1915 and Cairnes Brewery in 1908. Tragically these sometimes involved two or three fatalities, as one person went down to aid the other as happened in Clonmel Brewery in 1916, when three worked climbed into a vat one after another to help the others and were overcome, only one survived.

TRAGIC CLONMEL AFFAIRTwo Brewery Workers Killed.A shocking tragedy occurred at the Clonmel Brewery resulting in the death of two workmen and the narrow escape of a third from similar fate. While a man named Michael Mc*** was engaged on a ladder washing, with a hose, a large vat, about 15 feet high, covered at the top, and entrance to which effected by means of a ladder through a trap door, he was overcome gas fumes and fell the bottom. Another employee, James R***, apparently climbed down to the rescue, but was likewise overcome and a third, P. C*******, followed also for the purpose of rescuing his fellow-work men, but he too was overcome. Further help was quickly at hand; holes were bored in the sides of the vat to let in air, and, eventually, the three men were pulled out, and placed on the top where, under the directions Drs. Wynne, O’Brien, and Murray, artificial respiration was employed for several hours. C******* recovered under this treatment, and was sent hospital, but all efforts to revive Mc**** and R*** were unavailing. Distressing scenes were witnessed as the bodies were removed to the Morgue, the wives and relatives giving vent their grief. Rev. W. Walsh, C.C., was promptly in attendance and climbed to the top of the vat to minister to the unfortunate fellows. Both of the victims were married, R*** leaving a large young family.

The same calamity happened in Manders brewery in 1882 where one of the three men died.

FATAL ACCIDENT IN MANDERS' BREWERY

On Saturday evening three men, named George D****, Patrick R*****, and Patrick J****, were working on a loft in Messrs Manders' brewery, 113 James's street. D**** went in to a vat for some purpose, and was immediately rendered insensible by the carbonic acid gas. R***** and J**** went to the assistance of D****. and were themselves immediately overcome by the gas. In the meantime the three men were missed, and with great difficulty got out with the aid of ropes. D**** was found to be dead, and the other two remain in a precarious condition.

Reports of these types of deaths used words such as ‘foul air’ or ‘gas fumes’ or ‘spirit’ as well as ‘carbonic acid gas,’ so it appears that many breweries were aware of the issue but didn’t have the terminology or knowledge to know exactly what was the cause in the very early reports, although it appears to have been common practice to lower a candle into the vats, as it would be extinguished by the presence of this ‘foul air.’ There are also mentions of the need to open taps - or bore holes in an emergency as mentioned above - to let air in, or probably more accurately as we now know, to let the heavier than air carbon dioxide flow out.

-o-

Outside of the brewery could be a dangerous place to be working for the brewery too, especially if you were a drayman who hauled beer around the country to the various public houses or bottlers. Drivers lost their lives on occasion in accidents such as one drayman for a Dungarvan brewery who in 1870 was killed when his cart collapsed and he was pitched forward into the space between the horse and the front of the vehicle, where he was kicked to death by the animal as it tried to extricate itself. He left a wife and six children to mourn his untimely end.

A young driver from the Macardle Moore brewery in Dundalk who was delivering ale to the local military barracks in 1868 was killed when his horse was startled by the sound of a trumpet and bolted. The unfortunate individual was run over by the wheels of his own cart as he attempted to catch the reins to stop the horse.

A driver for Perry’s brewery in Rathdowney drowned in a water-filled ditch near Cuddagh Bog when the cart he was steering overturned and trapped him beneath it in 1905, and a similar accident occurred much earlier in 1829 when a drayman for D’Arcy’s brewery was drowned while attempting to rescue his horse which had ended up in the canal at Ringsend, and both man and beast perished.

But it wasn’t just drivers that were killed as can be seen from the following incident involved a young drayman from the Creywell brewery in New Ross owned by Cherrys.

FATAL ACCIDENT

During the Quarter Sessions in New Ross, an old man named P****, a farmer, from Misterin, county Wexford, was knocked down outside of the Courthouse by a local brewery van, which rolled over him, and killed him almost immediately. The driver of the van, a boy named Peter W*****, was immediately arrested and remanded. The evidence up to the present show that the deceased was more or less intoxicated - that there was [sic] some cars down the footpath outside the sessions house railings, which made the narrow lane still narrower - that W***** was driving the brewery horse (which is blind) at the rate of about six miles an hour, and did not slacken his pace coming around the corner of Cross Lane; that the deceased was crossing the lane obliquely, when the "off" shaft struck him, and when the people shouted out to the driver to stop, he pulled up, just as the wheel had rolled up from the unfortunate man's abdomen to his neck, and that he died almost immediately. Mr Colfer, solicitor, is engaged for the relatives of the deceased, and Mr Hinson, solicitor for the defence of the prisoner. Mr Carey, D.I., R.I.C, prosecuted. Bail was refused.

It would be hard to decide here whether the drunken individual, the speeding driver or the blind horse were to blame.

Sadly, small children were killed by brewery drays on at least two occasions, and there were probably even more fatalities than that. In 1899 a float belonging to Mountjoy brewery in Dublin was involved in an accident with a two-year-old boy which resulted in the loss of the child’s life, and in 1912 a three-year-old girl was killed near Bow Bridge, also in Dublin, having been run over by a dray belonging to D’Arcy’s brewery when she ran from a shop and tumbled under the wheels of the cart.

Staying with transport there have also been a few fatalities related to steam engines, with crush injuries and other accidents known to happen. For example, in 1889 a driver died on the narrow gauge in the Guinness brewery when he was knocked from his engine in a tunnel while driving between the brewery and the quay. He was crushed between the wall of the tunnel and his locomotive.

Even tugboats plying the Liffey were not completely safe, as in 1879 an employee of Guinness who was working on the steam tug Lagan was drowned after the boat hit the central arch of the Queen Street Bridge – now called Mellows Bridge - and he was thrown into the river with a companion, who survived.

-o-

Stranger incidents occurred too, such as the death in 1891 of a man in Kilkenny from rabies he contracted from a dog who ran into Sullivans’ James’s street brewery.

DEATH FROM HYDROPHOBIA

In the Moderator of Saturday but we stated that a man named Martin M*****, who was employed as a vanman in the James's-street Brewery. Kilkenny, was lying so dangerously ill in the workhouse hospital with an attack of hydrophobia that he was not expected to recover. We regret to state that the poor fellow expired early on Saturday morning last. One day in March last, it may be remembered, a dog - which it was afterwards discovered was suffering from rabies - ran into the yard of the James’s-street Brewery, where poor M***** was working. The dog ran towards M*****, and on raising his hand to keep the animal back, it immediately snapped at him and bit him on the finger. Information was at given of the to the James's- street police. and early the following morning the dog was destroyed, Mr. John Barry, V.S.. having pronounced it to be suffering from rabies. M*****, on hearing this. did not, as he should have done, place himself under medical treatment, but continued, poor fallow, from day to day at his usual employment until last Wednesday evening, when he was taken suddenly ill. Dr. Hackett was immediately sent for, and he at once stated that M***** had developed symptoms of hydrophobia, and ordered him to be removed to the hospital of the workhouse. Hydrophobia is, according to one of the highest medical authorities, a disease from which scarcely any person has ever been known to recover, and but little hope was entertained of the unfortunate sufferer's recovery. From Wednesday evening be continued to linger on until Saturday, when, as we have stated, he expired in great agony. The greatest sympathy is entertained for the deceased man's wife and family in their bereavement, and the large assemblage of the general public at his funeral on Sunday last testified to the high esteem and regard in which the deceased was held. It is a most unfortunate thing that a human life should be thus lost, merely by not having a strict law enforced as to the muzzling of dogs, and it is to be hoped that the authorities will take such steps in future as will prevent a similar dreadful occurrence.

As seen above, brewery horses died on occasion too but in 1896 there was an unusual occurrence as reported below:

A HORSE STUNG TO DEATH

On Saturday last, the 20th instant, a man named Daniel Brennan, was dispatched from the firm of E Smithwick and Sons, St Francis Abbey Brewery, to the licensed premises of Mr T Kennedy, Bennettsbridge, Kilkenny, with a load of drink. He arrived there about six o'clock, and after he had made delivery, was about leaving for home, when quite suddenly, a whole hive of bees landed on the horse’s head and neck to begin their deadly havoc. Immediately the horse became frantic and dashed madly along the road for some distance, when he was with much difficulty brought to a standstill. Some helpers having arrived at the time, he was unyoked from the car. and put into an adjacent field. Here he lay down and remained in the most acute pain until the following morning, when he was got up and removed slowly along the road. He never rallied, however, and on Monday morning he expired after undergoing the most dreadful agony.

-o-

It is worth mentioning that in many cases in the deaths reported above there was a recommendation for the breweries to make some payment to the dependants of those who died, and it would be good to think that this was followed up on, or that there was payment made via The Workman’s Compensation Act which legislated for such eventualities. But it is also worth restating that these were all real people who died in tragic circumstances, but with each death it could be hoped that steps were put in place to lessen the risk of a reoccurrence of such a tragedy in the future. The outcome can perhaps be seen in the opening quotation from Guinness’s The Harp magazine - a brewery that has seen its own fair share of those deaths as we saw - where at least there was a rapid response if an accident did occur, and presumably more preventative procedures in place too.

I know many people love a ghostly story, so maybe some think that a form of essence, or possibly a life-echo reverberation, still inhabits the brewing-related (and other) places where these deaths occurred. Perhaps they think that a small part of the dead's souls live on even still, although many of the locations are now homes, offices or just empty spaces. But whatever our thoughts on whether ghosts exist or not at least these unfortunate people live on in one way in the faded ink of newspapers - or in pixels and 1s and 0s - for ever, perhaps. They are fact not fiction.

Stories are just that, tales for entertainment be they ghost related or not, but death is real.

So brewers, be safe.

Liam K

(I have deliberately left out a couple of deaths I came across, as even though much time has passed they are connected to living, known descendants. I have also left out any mentions of self-harm or murder, and I have purposely doctored the surnames of victims in newspaper reports. As someone whose great-grandfather met a gruesome machinery-related death over a century ago, the subject and thought of his name appearing in an ‘entertaining’ article might make me or my family members feel uneasy, hence my reticence to use those last names.)

Please note, all written content and the research involved in publishing it here is my own unless otherwise stated and cannot be reproduced elsewhere without permission, full credit to its sources, and a link back to this post. The photograph and magazine itself are the authors own and the image cannot be used elsewhere without the author's permission. The actual magazine was published by Guinness for its personnel, which allowed use such as I have done here according to the notes inside the front cover. Newspaper research was thanks to The British Newspaper Archive and the exact sources for the deaths and quotations mentioned and shown above can be requested from me via email or message. DO NOT STEAL THIS CONTENT!

.jpg)